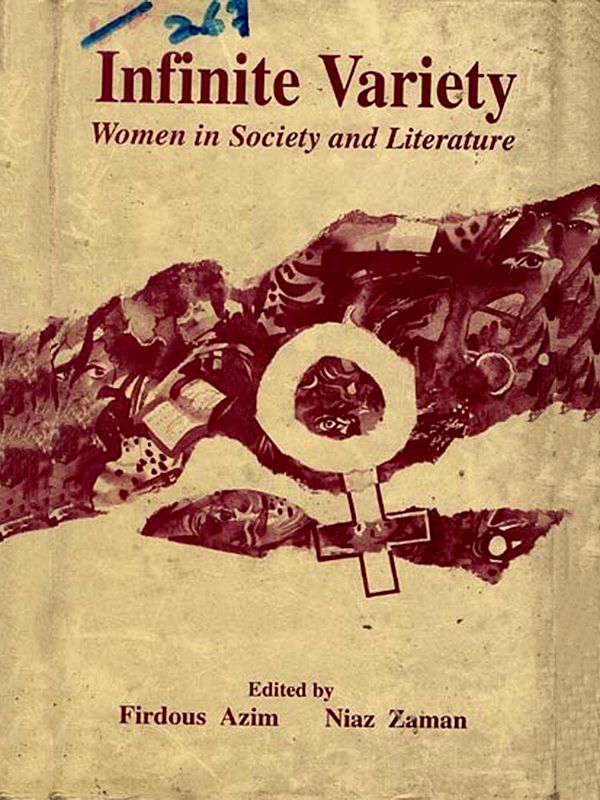

Infinite Variety Women in Society and Literature (An Old and Rare Book)

| Specifications |

| Publisher: University Press Limited (UPL), Dhaka | |

| Author Edited By Firdous Azim, Niaz Zaman | |

| Language: English | |

| Pages: 382 | |

| Cover: HARDCOVER | |

| 9.00x6.00 inch | |

| Weight 590 gm | |

| Edition: 1994 | |

| ISBN: 9840512528 | |

| HBT685 |

| Delivery and Return Policies |

| Returns and Exchanges accepted within 7 days | |

| Free Delivery |

But, you may say, we asked you to speak about women and fiction-what has that got to do with a room of one's own? The opening passage of Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own (1928) plunges the reader directly into the complexities of the relation between women and writing. The "variety" in our title-Infinite Variety-adds to this complexity the many facets and questions that arise whenever the subject of women and writing is broached. It is impossible, as Virginia Woolf found at the beginning of the century, to talk about women and writing without bringing in the broader issues of women's position in society and culture.

Feminist literary criticism traces its roots to the wider feminist movement, and insists on keeping intact the connections between the literary text and the social and psychical realities in which it has its foundations. In the first instance, feminist literary criticism had been marked by a celebration of women's writing. It drew a straightforward and linear connection between the text and the woman writing or reading, and envisaged an ideal community of women, drawn together through women's writings. Elaine Showalter, perhaps the most influential writer in this phase of Anglo-American feminist critical practice, calls this a "gynocritical" approach to literature.

The emphasis on the difference between men and women in literary representation that this approach first brought forward had the very significant effect of undermining the concept of universality. Literature's universal appeal-the uniformity of response that "great" literature demanded-was put to question, and its differentiated address was highlighted. But while women readers of literature put the established "greats" to the test of gender differentiation, they became embroiled in the similar task of preparing another list of great texts-the woman's text. A new set of novels, with some poetry, was now presented as containing the "truths" of women's lives, and a universality of appeal sought for these writings.

But, as feminism's focus on difference has taught us, literary texts do not have the same address for all, and differences between women are as important and as determining of social and subjective positions as differences between men and women. The connection between the text and reality is also not an innocent one, and the notion of literature as a straightforward reflection has never been able to stand its ground. Class-based and racial difference gain equal importance in the study of women's writing. An unearthing of women's writing reveals that it is the middle class woman, with access to education, who achieved the facility to write, and who could think of getting her work published.

Thus, feminist literary criticism ranges over a varied and heterogeneous field. One of its strongest areas is informed by an archaeological impulse, as critics and historians delve under the surface to dig for hidden literary gems. This project is often associated with history, and is involved in reinscribing women into the pages of history, literary and otherwise. In England, for example, the Pandora Publishing Press has undertaken, since 1986, the publication of lesser-known, even unknown, writings by women in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Under the title "Mothers of the Novel," this series performs a literary-historical task and aims to provide for women a literary genealogy and identity.

-

Q. What locations do you deliver to ?A. Exotic India delivers orders to all countries having diplomatic relations with India.

-

Q. Do you offer free shipping ?A. Exotic India offers free shipping on all orders of value of $30 USD or more.

-

Q. Can I return the book?A. All returns must be postmarked within seven (7) days of the delivery date. All returned items must be in new and unused condition, with all original tags and labels attached. To know more please view our return policy

-

Q. Do you offer express shipping ?A. Yes, we do have a chargeable express shipping facility available. You can select express shipping while checking out on the website.

-

Q. I accidentally entered wrong delivery address, can I change the address ?A. Delivery addresses can only be changed only incase the order has not been shipped yet. Incase of an address change, you can reach us at help@exoticindia.com

-

Q. How do I track my order ?A. You can track your orders simply entering your order number through here or through your past orders if you are signed in on the website.

-

Q. How can I cancel an order ?A. An order can only be cancelled if it has not been shipped. To cancel an order, kindly reach out to us through help@exoticindia.com.